An unnamed grave in Bomana War Cemetery near Port Moresby is the last resting place of an Australian officer murdered by so-called ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’, his family believes.

Lieutenant Hercules ‘Herc’ Crawford disappeared amid a skirmish during the early days of the Kokoda campaign of World War II in what is now Papua New Guinea.

Crawford was heroically repelling the Japanese army in the 1942 ‘Battle for Australia’ when he lost his life, but the location of his remains has been unidentified for more than 80 years.

Now an independent researcher says he can conclusively show the father-of-three from Port Adelaide was eventually buried at Bomana and his descendants want his headstone to carry his name.

Brenton Brooks provided the results of his investigation to the authority responsible for finding, recovering and identifying Australia’s missing war casualties but more than a year later no determination has been made.

His work has also challenged the universal perception of wartime Papuans as friendly allies who selflessly cared for wounded Australians, earning their Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels nickname.

Crawford’s granddaughter Natasha Read hopes Brooks’s work will lead to the Army finally recognising her ancestor’s grave.

‘It has been a very long and windy road to get where we are today,’ she told Daily Mail Australia.

An unnamed grave in Bomana War Cemetery near Port Moresby is the last resting place of Lieutenant Hercules ‘Herc’ Crawford, who was murdered by so-called ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’ during the Kokoda campaign of World War II, his family believes

Brooks says while the Army lists 18,000 Australians who fought in France and Belgium in World War I as missing, the 2,200 men unaccounted for from the PNG region in World War II have been ‘forsaken’.

He says that unlike the U.S., which operates the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Australia does not actively seek to find its missing war dead in foreign territories.

Instead, a body established in 2010 and called Unrecovered War Casualties – Army (UWC-A) focuses on identifying already located remains.

In the case of identifying Crawford, Brooks has accessed previously underutilised archival material to uncover decades of overlooked evidence, wrong assumptions and outright mistakes.

To understand the previous confusion about where Crawford was buried, Brooks needed to consider the fate of two other missing Australian officers from the Kokoda campaign.

Following Japan’s attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbour in December 1941, its imperial army began sweeping through South-East Asia and the Pacific.

Losses in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 thwarted Japan’s seaborn invasion of Papua through Port Moresby. It subsequently sought to take the territory by land from the north coast, over the Owen Stanley Ranges.

Standing in the advancing Japanese army’s way were soldiers from the now-famous 39th Battalion – then an untested militia force – and elements of the locally raised Papuan Infantry Battalion.

Herc Crawford’s death complicates the image of Papuan stretcher-bearers known as Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels. This iconic image shows a blinded Australian soldier, Private George Whittington, being led to a field hospital near Buna by Raphael Oimbari

Among the officers in the 39th Battalion were Crawford, who had fought with the 7th Division in North Africa as a ‘Rat of Tobruk’, and Captain Samuel Templeton, a World War I veteran who had served with the Royal Naval Reserve in the Adriatic Squadron.

Templeton, who according to a contemporary had ‘determination to excel at leading and protecting his troops in action’, was defending a position east of Kokoda at Oivi on July 26.

Concerned a smaller group of Australians was exposed to ambush, he left his men to warn the others and refused an escort.

After Templeton set out alone, Private Charlie Pyke described seeing him ‘snatched’ by two heavily camouflaged Japanese soldiers.

Japanese documents later revealed Templeton was one of two prisoners captured that day and that five more were taken shortly afterwards in the first Kokoda engagement.

No Australian soldiers who fought on the Kokoda Track survived capture and at the end of the campaign 177 were still missing. No Japanese were ever tried for killing prisoners in Papua.

Brooks has built on the work of 39th Battalion historian Carl Johnson to establish what happened to Templeton using evidence produced in war crimes investigations, personal memoirs and the official Japanese history of events.

Upon capture, Templeton was interrogated and under questioning falsely claimed there were 20,000 Australian troops awaiting the invaders from Kokoda back to Port Moresby.

This picture taken by acclaimed photographer Damien Parer of six soldiers slugging their way along the Kokoda Track is one of the defining images of the World War II campaign

Sergeant Imanishi Sadashige said Lieutenant Colonel Tsukamoto Hatsuo became so enraged with Templeton inflating the Australian force’s strength he stabbed him in the stomach.

Another Japanese soldier, Nishimura Kōkichi, said he found Templeton with a large knife sticking out of his side and buried him near a waterfall at Oivi.

After the Japanese had taken Kokoda, the Australians – including a platoon led by Crawford – launched a counter-attack to retake the village on August 8.

During this action, 34-year-old Crawford was hit by a bullet which grazed his temple and another which entered his thigh.

Crawford left an aid post to walk the six hours to the battalion’s base at Deniki, his head swathed in blood-stained bandages, a stick in one hand and a revolver in the other.

Two runners sent to escort Crawford caught up to him after two miles but were sent back by him to resume fighting. When his unit got back to Deniki, Crawford was not there and was presumed to have met with misadventure.

Chaplain Norbert ‘Nobby’ Earl later revealed he and Lance Corporal Sanopa of the Royal Papuan Constabulary had seen Crawford ‘jumped’ by local Orokaiva men.

Earl said the pair witnessed about 15 ‘natives’ surround an officer with a heavily bandaged head and thigh who was waving a pistol above his head. The officer had been knocked to the ground with tomahawks and carried into the jungle.

At the end of the Kokoda campaign, three Australian officers were missing: Herc Crawford, Captain Samuel Templeton (left) and Captain Arthur ‘Dasher’ Dean (right). Brenton Brooks is confident he has identified the final resting places of off three men

Indigenous men had been forced to reconsider their loyalties as the Australians retreated. Sanopa later pointed out six of the Orokaiva perpetrators, whom he said worked for the Japanese. All were tried and hanged.

Brooks notes that ‘obviously, loyalty for civilians was a gamble when choosing the winning side while under occupation during war’.

‘The murder of an Australian soldier by local men is a sensitive issue of culture and identity,’ he writes in his paper.

‘This complicates the notion of Papuans as indigenous carers, often referred to as Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels, shown in historical newsreels carrying or assisting wounded soldiers and still depicted in this way in the current Anzac narrative.

‘Praising indigenous stretcher bearers was a symbol of the partnership between the Australians and Papuans against the Japanese.

‘Betrayal of Europeans by the indigenous population caught between two ruling powers was more common, however, than has been recognised.’

After Kokoda had been retaken, an almost complete skeleton of an officer was recovered from near where Crawford had been killed.

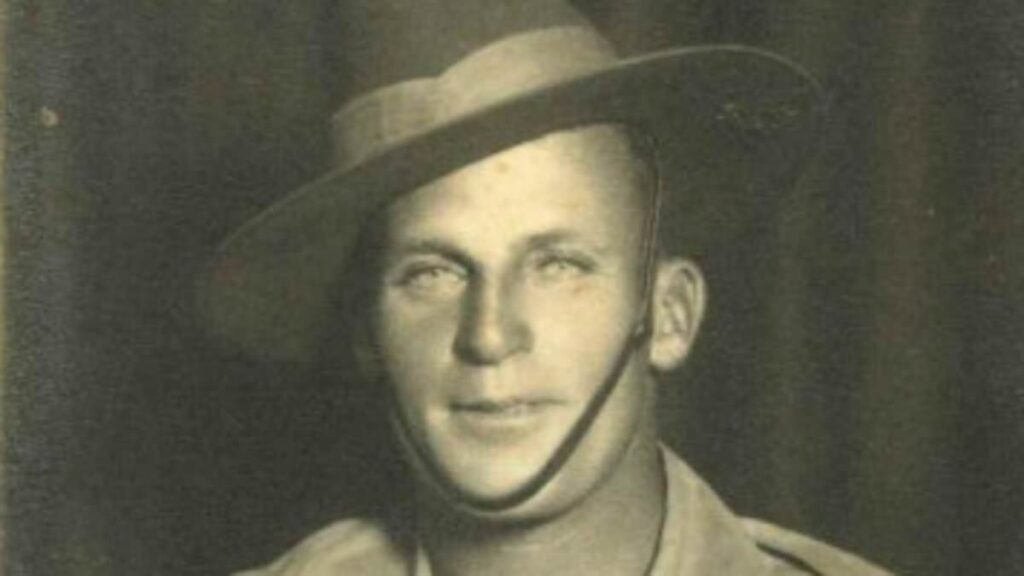

Herc Crawford (above) came from South Australia and and fought with the famed 7th Division in North Africa as a ‘Rat of Tobruk’ before being sent to Papua with the 39th Battalion

The Australian War Graves Unit concluded that without evidence such as dog tags those remains could not be be positively identified. They were buried at Soputa War Cemetery as an unknown soldier and later reinterred at Bomana in grave C.6.B.25.

It was not until the war was over, in 1946, that Templeton was officially presumed to be dead.

After the final peace treaty with Japan was signed in September 1951, the defeated nation’s government was given permission to recover its soldiers’ remains from Papua.

‘It seems that this process of recovery wrongly included Templeton’s remains,’ Brooks writes.

Records of Japanese grave sites in Papua show a single skeleton was located in a field burial matching where Nishimura Kōkichi said he buried Templeton. That grave was empty when examined in 2010.

Six further unidentified bodies were surveyed in a nearby grave which might represent the other Australians captured and executed at the time Templeton was killed.

The Japanese War Graves Missions has a policy of exhuming unidentified remains for repatriation and cremation. Brooks thinks it likely the ashes of Templeton and his six comrades are in an urn at Japan’s National Cemetery of Unknown Soldiers.

Researcher Brenton Brooks has identified this grave at Bomana War Cemetery near Port Moresby as the last resting place of Lieutenant Hercules William Crawford

The only other Australian officer listed missing from the Kokoda campaign was Captain Arthur ‘Dasher’ Dean who was buried where he fell at Faiwani Creek on August 8, the same day Crawford was killed.

Chaplain Nobby Earl, who had given Dean his last rites and presided over his burial, returned to Kokoda with the 39th Battalion Association in 1967 to locate and mark his grave.

‘The online records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission state that Dean was not recovered and is still commemorated as “missing” on the Port Moresby Memorial,’ Brooks writes.

‘Based on probability, therefore, the unidentified Bomana grave C.6.B.25. is likely to be that of Lieutenant Hercules Crawford.’

Crawford’s Korean War veteran son Fred sought information from the Army in 1953 about his father’s fate. He died aged 83 in 2016, having been told no explanation was available.

The family has continued to seek answers and has put its case to Unrecovered War Casualties – Army that grave C.6.B.25 at Bomana holds Crawford’s remains.

Consideration was given to the Crawford family providing DNA samples but the Commonwealth War Graves Commission does not permit exhumations.

Brooks says identifying Herc Crawford’s grave would provide answers for his descendants and his last surviving comrades.

A Royal Australian Navy sailor is pictured walking among the graves at Bomana War Cemetery. The family of Herc Crawford want the grave they believe holds his remains to be named

‘It’s all about resolution for the families,’ he tells Daily Mail Australia.

‘Restoring the name on an unknown grave gives the soldier their identity back and provides closure for the family.

‘The Crawford family have waited over 80 years for resolution. Herc’s son, Fred, spent his lifetime trying to establish what happened to his father. He sought answers. Officialdom failed.’

Crawford’s granddaughter Natasha Read said her family just wants their ancestor’s sacrifice to be acknowledged with his name on a grave.

‘That’s all we want now we know where he is,’ she said.

‘We just want his name on a plaque. We don’t want him missing in action anymore.’

The Army has been contacted for comment.